The Book of Visitations of Glory

Issue Six

Usenánu: The Great and Powerful City of Two Rivers

Located near the convergence of the Arjáshtra and Missúma rivers, this ancient city sits in the center of the breadbasket of the Empire. The production and distribution of foodstuffs begins here and extends out to all parts of Tsolyánu and beyond.

It is one week before the Intercalary Days and the view from my guest quarters at the Temple of Avánthe is beautiful. The sky blue roof combs, with gilded edges of gold, tower over the many adjacent buildings. Usenánu’s picturesque ancient gray walls undulate up and down around its perimeter serving as a ring band. The strongholds of the other gods are set around like colorful sidestones to the central gem of this temple.

Outside the northern wall are the low White Feather hills. The nearer rises are burrowed everywhere for the dead. A thin blue veil of haze covers them in the glory of the early morning light. All memories of disappointment vanish before this wealth of light.

The central part of the city is filled with streets of staid, aristocratic dullness inhabited by wealthy merchants. I spent some morning hours in the nearby central haudárukh; thronged with humans and other species from morning till night with only a short break around noon to escape the oppressive heat. Here representatives from the various clans show samples of their wares. The actual production of these goods is performed at the respective clanhouses located on the specialty streets scattered throughout the city. Most orders taken here are for large quantities to be delivered later, or are for sale to the neighboring population who do not wish to travel across the city.

Two dháibakh is the standard width of the street, and between the passersby, the loungers, the people standing at stalls bargaining, and the marching troops, traveling through the city can be difficult. Passage through the crowd was one long gentle push as the participants automatically scanned each other for status and decided who gave way to whom. Once, as my hired bearers were elbowing a path through the surrounding horde, I was surprised by a loud yell, and being gracelessly hustled out of the way, I became aware that the crowd has yielded to a procession, consisting of several ceremonially armed men in white, followed by a handsome closed palanquin, borne by eight bearers in white livery, in which reclined a stout, magnificently dressed Patriarch of Hnálla, utterly oblivious of his inferiors. The representative of high position, he was reading and never took any notice of the crowds and glitter which I find so fascinating. More men in white followed, and then the crowd closed up. After chastising the bearers for their clumsy attempt to get out of the way, the crowd was again divided by my middle clan chair. Other groups vying for openings included Belkhánu temple workers running with a coffin three dháibakh long, shaped like the trunk of a tree, and slaves carrying burdens slung on poles, uttering deafening cries, a marriage procession with songs and music, and a funeral procession with weeping and wailing, succeeding each other incessantly. All the people in the streets were shouting at the top of their voices, the chair and baggage slaves were yelling, and to complete the bewildering din the Avánthe priests at every corner were demanding piety by striking two blocks of wood together.

Color erupts in these constricted streets, with their high houses projecting upper stories over the throng. Their eaves are heavily carved and gilded in between the river shell tiles that let through a soft light to the streets below, while a sky of deep bright blue fills up the narrow slit between. In the near-shadow below, fitfully lighted by the sunbeams, hanging from all the second stories are the richly painted boards two to three dháibakh long. Some are black, some heavily gilded, a few orange, but the majority blue and perfectly plain, except for the glyphs several hóikh long identifying the clan down the middle of each, gold on the blue and black, and black on the gold and blue.

Now, the entire crowd is in holiday dress. The prevailing color is bright blue. Even the slaves put on such dress when not working, and all above the low clans wear them in rich, ribbed güdru, lined with thésun of a darker shade. And these prosperous-looking men, who are so richly dressed, are only the shopkeepers and the middle clans of merchants. The high clansfolk seldom put their feet to the ground and thus avoid soiling their fine gold-and-silver arzhúm.

The shops newly filled with all sorts of brilliant and enticing things in anticipation of the great festivals. During the Intercalary Days they are all closed, and the rich merchant clans vie with each other in keeping them so. Those, whose shops are closed the longest, sometimes even for two months, gain a great reputation for their wealth.

Near the temples the streets are given up to shops of one kind or another. Thus there is the "Jade-Stone Street," entirely dedicated to the making and sale of jade-stone jewelry, which is very costly and much desired by the Green-Eyed Goddess at the Lady’s nearby place of worship. There is a another whole street devoted to the sale of coffins; several in which nothing is sold but furniture, from common folding tables up to the costliest tables, bedsteads, and chairs of ma ssive serésh carving; pottery streets, book and engraving streets, streets of thésun shops, streets of workers in bronze, silver, and gold, who perform their delicate manipulations before your eyes; streets of tailors, where gorgeous mantles of khéshchal plumes can be bought ; and so on, every street blazing with colors, splendid with costume, and abounding with wealth and variety.

There are hundreds of butcher and fishmonger clans' shops in Usenánu. At the former there are always hundreds of split and salted fowl hanging on lines, and hmá of various sizes roasted whole, or sold in joints raw. The fish shops and stalls are legion, but the fish looks sickening, as it is always cut into slices and covered with blood. The boiled skin of a species of large worm is exposed for sale as a great delicacy, and so are certain kinds of hairless, fleshy insects.

In my wanderings I came upon a shop of the Green Opal Clan, with its vestibule hung with scarlet, the chosen marriage color of the wedding party. Within the door the "wedding garments" were hanging for the wedding guests, scarlet güdru cloth, richly embroidered. Some time later the bridal procession swept through the streets, adding a new glory to the color and movement. First marched a troop of men in scarlet who carried scarlet banners, each one emblazoned with the great deeds of the bride’s clan. Then came ten heavily gilded, carved and decorated pavilions, each containing marriage presents and borne on poles on the shoulders of slaves. After this display of glory and wealth, came the bride, carried in a locked palanquin to the bridegroom’s clanhouse, completely shrouded, the palanquin was one mass of decoration in gold and blue enamel, the carving fully ten hóikh deep. The procession was closed by a crowd of me n in scarlet, carrying the groom’s clan’s stern-faced dlántukoi, with banners, and instruments of music.

I have also visited the strange and ever-shifting waterfront, which is one of the most marvelous features of this city. Floating and stationary, with about one hundred thousand residents, its population is subtly distinct in race from the land population of Usenánu, which looks down upon it from its dome shaped heights. The hruchánmekh I have enclosed give a very good idea of the forms and colors of the boats.

A short distance below Usenánu’s city center the piers of the maritime clans maintain their large, two-storied clanhouse boats, with entrance doors two dháibakh high, always open, and doorways of rich wood carving, through which the interiors of the first deck can be seen with their richly decorated altars, innumerable colored lamps, sitting mats and tables of carved serésh wood with white marble set into the top. Embroidered thésun hangings, gilded mirrors and cornices, and all the extravagances of Tsolyáni luxury complete this display of wealth and power. Many of them have gardens on their roofs. These are called flower boats, and are fragrant and colorful. Then there are the outlying tiers of three-roomed, comfortable house boats used to avoid the summer heat and crowding near the docks. Marriage boats, with banners announcing the most recent union; long distance river transports, with their carved and castellated sterns; bird boats, with their noisy inmates; florist clan’s boats, with platforms of growing plants for sale; two-storied barges, with open sides, floating brothels, in which evening entertainments are given with much light and noise; food preparation boats, with soot covered gilt, from which proceeds an incessant stream of noise and cooking smoke; washing boats, market boats, floating shops, which supply the river clans with all marketable commodities and services; boats from Béy Sü, Haumá and Jakálla of fantastic form coming in on every wind and current.

There are fishing craft with big, stylized eyes on either side of the bow, without which they could not see their way. These unwieldy- looking vessels are sailed with an amount of noise and apparent confusion which is absolutely shocking to anyone unused to nautical travel. The rudder projects astern one and one-half dháibakh or more, the masts are single poles, the large sails of fine cloth; and what with their triangular shape, rich coloring, lattice work and carving are the most pleasing craft afloat. Then there are "passage boats" that service the sákbe road crossing and the entire network of rivers and canals, each clan having its special rig and build, recognizable at once by the initiated. These sail when they can, and when they can’t are propelled by large sweeps, each of which is worked by six men who stand on a platform outside. These boats are always heavily laden, crowded with passengers and they carry crews of from thirty-five to fifty men.

Unlike the dilapidated dwellings of the nearby poor clans on shore, the clanboats are models of cleanliness, and space is efficiently utilized. These boats, which contain neat rooms with matted seats by day, turn into beds at night. The children have separate quarters. The men go on shore during the day and tend to the clan’s work, but the women seldom land and are devoted to their own duties. However, in the transport clans the women have a more visible role. They are seen at all hours of day and night flying over the water, plying for hire at the landings, and ferrying goods and passengers. As strong as men, they are clean, and pleasant-looking. With one at the stern and one at the bow, they send the hull along with skilled and sturdy strokes. Their dress is made from a simple dark brown or blue cloth. The feet are big and bare; the hair is neat and drawn back from the face into a stiff roll that accentuates the display of their large turquoise ear plugs. These women often ply the heavy oars with a wise- looking baby on their backs, supported by square pieces of blue cloth embroidered in gold and red thésun.

I went to several temples which have priestly dormitories attached to them, with great tidy gardens and ponds fo r sacred fish. The temple of Avánthe even has houses for sacred hmélu, whose sacredness is shown by their monstrous obesity. Each temple has an accretion of smaller temples or shrines round it, but most, just before the Intercalary Days, are deserted. Where I saw worshipers they were always women, some of whom looked very earnest, as they were worshiping for sick children, or to obtain boys, or for the fortune of their clan. Priests and priestesses were always available to the worshippers for guidance in the rituals. Other clergy were concerned with obscure ceremonies to their gods such as the priest in front of the Temple of Thúmis who has a growth like a horn his forehead, with which he struck the pavestones and produced an audible thump.

In the district of the Temples of Change is the outer court of the "Sanctuary of Pleasures," which is surrounded by a number of grated cells containing life-sized figures of painted wood, undergoing at the hands of other figures such torture as are decreed for certain ceremonies to Hriháyal. In the evening there is a perpetual crowd of fortune-tellers and numbers of various gaming tables always thronged with players.

Such sights remind me of my own duties back at the temple of “The Maiden of Beauty” where I must now prepare for the twilight ceremonies.

Local Usenánu Festivals During the Intercalary Days

Although Usenánu has the reputation of being a rather staid city, seemingly concerned only with the agricultural bounty of the plains and the making of money, it does offer some unique opportunities for revelry. The following ceremonies celebrate the transition between one point of existence and the next. It is a time of renewal for some, a time of inimitable demise for others.

Temple of Hnálla

Dawn of Ikáner. In the year 1843, during the reign of Nrainué, “the Iridescent Goddess”, and after the city’s ditlána, the powerful Emerald Girdle clan commissioned the famous artist Ayéla to construct a door for the renewed Temple of Hnálla. It was to glorify the god and to celebrate the retaking of Pán Cháka from the Mu’ugalavyá the previous year. She was to do whatsoever she desired and it was to be designed so that it would be the most perfect and most beautiful imaginable. She took 23 years and did not disappoint. Her doors are worthy of being called the “Gates of Opening Unto the Ultimate Light”. During this celebration the Emerald Girdle clan provides clothes and food to the worshippers as a sign of the clan’s great wealth, status and piety.

Temple of Vimúhla

Sunset of Vraháma. The ceremony of “The Wakening of the All-Cleansing Blaze”. Ancient beliefs teach that the gods must be reminded and shamed into performing their expected and required duties as the great powers that they are. Only voluntary sacrifices are accepted for this ritual. Usually they are Usenánuyani who are allowed to abrogate all debts to the temple by participating. After gathering together outside of the temple in the still darkness of early morning, they are led through the foreboding fortress gates, across the expansive red marble tiled plaza to the foot of the steep stairs that lead up the side of great pyramid. Above, the raging furnace known as “The Great Flame” awaits them with its eager caresses. The first ritual washing by their own clan members cleanses them of their indebted status. The second washing, conducted by temple acolytes, prepares the sacrifices for the transition and includes a sedative from drinking the water that the consecrated tetkúmne knife has been dipped into. Calmly they walk up the intricately carved steps and as they ascend the accompanying priest explains to them the meanings of the various levels as they reach them. The higher they go the more the drug takes effect. They actually experience the passage from this life to the next. When they reach the top they are impatient to complete the journey and join their “Great Lord of the Final Conflagration”. After one final blessing, they gladly jump into the waiting flames with looks of bliss upon their faces. After the ceremony the family members return to their respective clan houses to recount the bravery that they have witnessed. They celebrate their cousin’s journey to the Isles secure in the knowledge that their honor is intact. The Flame Lord has been reminded of his duties.

Temple of Avánthe

This outer ceremoney takes place at the small cave shrine of Avánthe in the nearby sandstone hills north of the city. The geological formations are attributed to the Aspect Quyéla and represent the rich fecundity of this arable land. Following the tedious and formal opening ceremony and casting of spells, the crowd is overcome by the forces that have been released and they engage in a day long act of drinking and debauchery in the surrounding grainfields.

Temple of Karakán

Chitlásha, fater the day’s celebrations of military pageants and displays and before the setting sun, the ceremony of "The Flight of Scarlet Missiles" is performed. All archery students of the temple’s "School of Feathered Lightning" participate. A warrior, chosen for his devotion and skill, shoots the victim (who is tied with arms and legs apart on crossed poles) with a sacred arrow. As the victim’s blood slowly flows down his body the audience anticipates the moment that it first drips onto the consecrated earth below. The audience holds their collective breath as the hear the drawing back of the remainder of the bows. As the first drop of blood penetrates into the soil, every student who has never claimed a kill can loose their volley of death. And finally, a third volley is fired by the rest of the participants, and a great cheer of exultation is heard throughout the temple plaza and nearby environs. Prayers are said, and the crowd turns to the great feasting tables to begin the celebration of this rite of passage. The newly-blooded warriors are welcomed into the temple for further initiation.

Temple of Dlamélish

Upon the first tolling of the tunkul of Ikaner, announcing the beginning of the Intercalary Days, young women under the age of twenty, are inducted into the "Oblection of Fleeting Glory". They have chosen to decline the comfortable, unbroken extent of society and thus are freed from the constraints of their previous positions. They may eat at the tables of any clanhouse and lie with anyone that offers themselves without proscription. They freely adorn themselves with the jewels of the temple, and dance and sing their songs of earthly transcience. Their deaths are mourned with the ceremonial formality reserved for only the highest clergy of the temple. They are a communcal demonstartion of doomed youth and beauty. They are allowed this unfettered existence until the end of Chitlasha when they are brought back in an extravagant procession to the main temple and from there led into the tsuru'um to the Shrine of Shu'ure "She of Great Exhileration". There they perform the final ritual not once, but several times each with five, ten or even twenty worshippers of Dlamelish and Hrihayal.

Then they die.

Their bakte and pedhetl fully consumed.

No more then sunken eyes,

Grey tresses, nasal mucus haanging.

A trembling of limbs

Rumpled flash hanging from bones.

Temple of Sárku

At midnight of Vraháma, the High Priestess at the trapezoidal Pyramid Shrine of Batha'ák, signals the gathered young athletes to begin the "Ceremony of Journeying Through the Tomb". The participants race to the altar to be the first to plunge their hands into the great trough of ashen chalk and pale bone-white feathers, and to toss the pulverulent mixture high up in the air so that they and their companions are slowly dusted with the color of sacrificial death. They run individual routes, following dark, secretly marked paths across the city towards the great Temple of the Worm Lord. Their seemingly chaotic windings through the streets and alleyways bring them past the mute stone monuments of past power to remind them of the inevitability of the unutterable stillness of death. Once outside of the sancitity of the shrine the racers are bound by few rules. They must pass all of the designated points on their unique paths and all actions must be done in perfect silence. Battles between intersecting opponents are not uncommon and the noiseless fights are unnerving to the spectators peering down from their clanhouse windows. Death is an acceptable outcome to these conflicts. The first to reach the temple is honored with a place aat the top platform as the representative of their noble ancestors during the nightlong feast.

Temple of Grugánu

Midnight of Ngaqómi, after the ceremony of "The Unsealing of the Gates of Night". High ranking followers of this dread Lord may observe the final exam at the College of Ancient Devices. Deep below the True Servitor’s squarish temple, around the heavily warded top edge of a dimly lit arena of black sand, they drink their Master’s dark wine and watch the challenge played out below them. The "Candidate for Enlightenment" enters the great pit and approaches the table near the centre. The disassembled parts of an "Eye of Raging Power" has been placed on the work surface. A glyph-laden instruction manual written in the obscure script of Duruób has been placed beside the mechanism for reference. In ten yóm, the horizontal doors in the center of the pitch will open and a pathway to the Citadel of the Twelve Pylons of Ta'lár is revealed. If the candidate has completed the assembly he may pass through that gate and visit with the Demon Qu'ú where he may be gifted with an ancient device to bring back to help the struggle to release the "Doomed Price of the Blue Room." failure to finish the task in the allotted time brings the shambling, multi-headed, sró-like visage of Tirragásche to aappear on the far side of the gate. The demon’s insectoid minions will rush forward through the gate and quickly feast upon the failed candidate. Judgement is seen as swift and sure. Successful candidates, upon their return, are honored for the remainder of the Intercalary Days with special feasts after which they will be sent, armed with new knowledge and their gifted device, to where they will be most effective in the final struggle.

From the Halls of the God of Engineers and Architects Under Seal of the High Prefect of the Temple of Keténgku in Usenánu.

‘Treatise of the Everflowing Water of Life’

The pure and fresh water, the heat and light shall circulate like the various fluids whose movement and maintenance are necessary to ensure life. The secretions will not mysteriously be placed there, and maintenance of public health shall be accomplished without disturbing the order of the city and spoiling its outer beauty.

Edict 1294

Governor of Usenánu

Since the settlement’s inception, its lifeline of water depended on the flow of the Arjáshtra and Missúma rivers. Over time, canals and great reservoirs were built to the north of the city to gather and hold the water and to provide a location for the “Great Headworks of Keténgku” that marks the beginning of the extensive plumbing system of city.

Human excretions of the order of 600,000 tsértse of urine and 200,000 tnáng of fecal matter per day require an adequate system of collection and disposal. The society, thus, has a constant threat of health hazards and epidemics. Potable water is available to everyone inside of the city walls and to most environs immediately outside the walls and the harbor area. Sewerage facilities are available to more than 70 per cent of the urban population in urban areas but only 10 per cent of rural population has access to flush latrines.

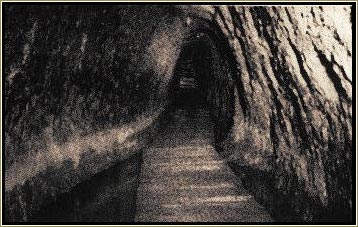

From the earliest times, water tunnels from the city tapped into the connection located just outside the northern city walls. As in other cities, access to the water supply had to be ensured against enemy invaders who conceivably could cut off the supply above ground. The early inhabitants initially tried to sink secure well shafts within the city walls, straight down to the water’s source, but couldn't. Their tools were no match for the hardness of the rock. Instead, they had to dig vertically and horizontally, first eking out a dark, angular tunnel. The tunnel descended by a treacherous flight of stone steps hewn from the rock; in essence a spiral staircase around a 10 dháiba shaft, down and around to a huge natural cave outside the original walls of the city. At the far end of the 17 dháiba long x 6 dháiba high x 3.5 dháiba wide cave, the diggers finally tapped the spring whose water still bubbles to this day far below the Great Temple of Avánthe.

The first major modification to the early city’s water supply was the excavation of a new tunnel even further away, to access water to the city, store the supply in an underground pool, and hide the entrance of the river. This was an attempt to thwart a possible siege of the city. Aqueducts are generally laid underground, sometimes to a depth of 14 dháiba. Some are broad enough to accommodate two men walking abreast. While the great cities of the plains are relatively flat compared to other Tsolyani cities, they still have the characteristic domed shape resulting from the process of ditlána performed over the millennia. The top level of the city has slowly raised itself up from the original pipes requiring new connections to be made to the sewers. The Wicker Image Clan is kept employed flushing the pipes and raising the potable water from the now very deep sources connected with the surface through large wells.

The low cartography maps on the next page were prepared to help guide the sweeper clan through the tunnels in order to perform their duties.

The actual construction of the water lines was epic in it proportion. During one excavation it took two teams of workers of the Black Hand Clan seven months to cut their way through 2 tsán of solid rock. Each team chipped the way to the center from opposite sides of White Feather Hill, extending an aqueduct from the new reservoir north of the hill to the city. Guided only by water fissures, they laboriously dug out a tunnelabout one dháiba in width, and one to three dháiba in height. One man wouldmethodically hack and chip away at the rock face and the others behind him picking up and passing the broken stones out in baskets. Chiseled in the rock at the point where the two teams met is an inscription recounting "The Opening Unto the Flowing Waters" in which the stone cutters made their way towards one another ax-blow by ax-blow. This day is still celebrated by the local clan.

Drains were built for removing sewage from clanhouses, palaces, administrative buildings and streets. They consist of a trunk line and auxiliary drains underneath the buildings. Waste and refuse from the buildings not hooked up to the sewer lines is carted out through the appropriately-named "Night Soil Gate" south of the city.

A typical large, high clan compound has a main sewer of masonry, which is linked to four large stone shafts emanating from the upper stories of the main building. The shafts act as ventilators and chutes for household refuse. The shafts and conduit are formed by cement- lined limestone flags, but earthenware or burnt clay pipes are used in the remainder of the system. These are laid out under passages, not under the living rooms. The drainage system consisted of semi- fired clay pipes, from 7.5 - 12 chóptse in diameter. The rain water overflow from the roof gardens and the courts are collected in cisterns below the bottom floors with the excess carried down further into buried drains. The pipes had perfect socket joints, tapered so that the narrow end of one pipe fixed tightly into the broad end of the next one. The tapering sections allowed a jetting action to prevent accumulation of sediment.

A medium clan bathroom often features decorated walls covered with monochrome frescoes and decorated friezes, and plaster stands which hold ewers and washing basins. Often, at the center is a pool with typical dimensions of 20 dháiba by 2 dháiba by 1/2 dháiba deep. There are surrounding slabs which form seats for the foot-bathers jutting over the bath. They are classically painted terra cotta, and decorated in a bas relief of a watery motif of reeds. The used water is discarded into a cavity in the floor and connected directly with the main drain.

Usually, not too far away is the flushing water closet, screened off by gypsum partitions on either side. Many are fitted with ventilating shafts. It is flushed by rain water or by water held in cisterns. There are holes in the floor, and beneath for flowing water. The stools are notched in such a way so that these can be used for defecation as well as urination. There are often several other closets found throughout the clanhouse too. The rich clans use hmá wool for ablution while the poor used grass, stone or sand or water depending upon the weather conditions. Amongst the lower clans it is very common to use water for ablution. People use the right hand for eating food, and it is considered disgusting to use the same hand for ablution with water. So the left hand is used for sanitary purposes.

Much attention has been given to constructing toilets on a pay and use basis in common areas where men pay per use, the females and children avail these facilities for free. The Temple of Keténgku has also set up primary health care center at these places.

Because the temples required their own "pure water" arrangements, there are two separate drain and waste water systems in the city. This was certainly an extra expense, but the temples developed a conservation system for its reuse. Basin water is channeled into temple ponds or large underground cesspools or directed into a settling basin. Here the waste materials are held in suspension and subsequently used as manure for the temple’s sacred fields and croplands.

Bathing Customs

As using hot water in Usenánu is considered effeminate, a man’s bath typically is a quick douse of cool water over the head. On average, his bathing basin is a waist high, polished marble bowl. Women’s bathrooms, on the other hand, usually contained portable earthenware tubs filled with warm water for a more relaxing soak.

The high clan Usenanuyani prefer cloths, oils, scrapers and rinses over the local type of soap which is manufactured from a combination of hmá fat and ashes.

It is considered good manners for a host to offer his guest the services of his bathroom after a dusty and arduous journey. Ah, the joys of being treated by a winsome slave girl as she scrapes his skin of perspiration and dirt with a bronze utensil. Ah, the shock when she completes her works with a good dousing of cool water from an urn setting on a stand nearby.

Other Customs

Other Customs

It is also popular these days to emphasize the medicinal values of human waste. Urine is supposed to have many therapeutic values. Some lay priests even claim that by study of urine they can confidently say whether a young girl is a virgin or not.

It is also widely believed that the dung of a hmá mixed with night soil removes black pustules on the skin.

For oral care it is advised to relieve oneself on one’s feet because the divine liquid gives the required cure.

If a warrior defecates too much, he will become weak because he has not digested all of what he eats. A member of the Flame-worshipping clans will deliberately block his anus during the ceremony of attaining of manhood and pretend as if he did not defecate at all.

Midwives predicted the future of the child from examining the first excrement.

Grandmothers often eat the first excrement of the male child if he was born after a long period of marriage or after number of female births in the

family.

Periodic "roaring" far underground is attributed to the bellowing of huge mythical worms, as they thrash about in the labyrinthine sewers below.

Usenánu Maps

Usenánu Central City Plan

Usenánu Central City Water Supply Layout

Usenánu Central City Sewer Layout

City Map Legend

Black lines are Primary Water Pipes

Blue lines are Secondary Water Pipes

Green lines are Primary Wastewater Pipes

Light green lines are Secondary Waste water Pipes